What’s the most famous photo of you?

Which image of you has had more influence than any other?

Chances are it’s a profile photo. You may not want to think about it, but that’s the image that the internet has of you. Of course that requires you to personify the internet, which is silly, but it makes you wonder what the profile picture of “the internet” might look like? And how it might change on different accounts.

We have lived through a period of extraordinary change. One hundred years ago if you had any photographic documentation then your passport picture may have been the only photo of you. Today I probably have more images of my three year old on one phone than exist of me in the whole world, a 40 year old parent. We are at a point where the profile photo is inadvertently at the frontline of photography, personal and brand representation. Selfies are personal, profiles are public. How many selfies do you see of some other self?

How easily can you bring to mind a friend or colleagues photo, or maybe they use their kids, or it is constantly changing, or they have someone famous, or just a picture of a rabbit? It is still them.

For many years my twitter profile betrayed me as a clumsily drawn cloud. And then later, for reasons that are now more obvious, a cartoon frog that I had drawn for an illustrated fairytale. There was a black and white picture of a stubbly white creative director type guy. There was the one of me, tanned, pretending I knew how to steer a boat. These and other images, collected together, are our avatars. Our unreal, virtual representative. Even if they are photo realistic, they are both us and not us. And to me they are the most important photos in the world.

This is my favourite internet-sourced interpretation of the notion of “avatar”.

“You might know this word from video games, where you create an avatar to represent you on screen. An avatar is something that embodies something else. In Hinduism the different gods can take many different forms, and when they took human forms, the human was their avatar. Eventually, the word avatar came to mean the embodiment not just of a god, but also of any abstract idea. If you have a cool head, you might see yourself as the avatar of reasonableness in a fight. Video game avatars are sort of a reverse of the first meaning — a physical entity (you) form becomes something abstract (a video game guy).

https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/avatar

So consider that for a second. Once you’ve got past the blue aliens thing, and the ‘cool head’ thing. Avatar is the most accurate word to describe the visual representation, the online portrait of all the different you’s. Your facebook you, your intranet you, your twitter you, your snapchat you, your insta-you’s, your gmail you, your whatsapp you, your grindr you, or, if you are trans-female like me, my tinder/okcupid/bumble ‘me’s. Maybe this seems like a simple thing. Maybe there is just one you. You are, after all, only you. But for many of us, especially in the trans community we will have spent some aspect of our life in disguise. The act of dissembling and hiding your true self is quite sophisticated. Far more so than the internet would like us to believe. Before the ‘real name’ controversy had even really got started in 2011, Chris Pool (Moot) had pinned down the complexity of self-representation online: “Google and Facebook would have you believe that you’re a mirror, but we’re actually more like diamonds. Look from a different angle, and you see something completely different… Facebook is consolidating identity by making us more simple than we truly are. We all have multiple identities. It’s part of being human. We’re all multi-faceted people.” Chris was the founder of 4chan and is now a Google employee, which kind of makes his point IRL.

It is always interesting when your villains turn out to be more sophisticated, thoughtful and intriguing than your heroes. In the real world just as in narrative fiction. One of the major issues with technology has been finding the line between the right to anonymity and being responsible for your words or actions in those spaces. Avatars or ‘all of your profile pics imagined as one thing’ are one place in which we visually seek to hide, disguise, signal, or just inform, or mis-inform. We represent ourselves visually as collections of very subtle ideas. Far more revealing in many cases than we may intend, or than the words we use in our written profile. In the queer community we are long used to the notion of tribal signalling, to engage through verbal or visual signalling both in our online spaces and offline — it has long been a matter of survival. Sometimes the fact that my dating profile literally begins: 👭 👫 ❄️ bi-, trans-,.. etc. gives me hope. That we live in a time with the potential for that radical transparency. And that for future generations they might not even need to flag their tribal affiliations, or their gender. In the meantime, it is a form of everyday activism, rather than virtue signalling, to define oneself in these media with simple declarative language. Out & proud I suppose.

Visually though, my avatar betrays a completely different story. In my assorted profile photos I aspire, not to queerness, or even generic human-ness but to the cis-gendered hetero-normative expectations that I was raised into. My professional profiles have me speaking at lecterns (albeit in a rather fabulous Comme des Garçons Kawakubo jumper). My social imagery spent the transition in stasis stuck with old photos in which I hid behind my children, or with cartoons, and then recently universally returned to a soft focus fashion-type image, professionally shot, with hair and make-up, of a woman leaning back against a wall, casually, nonchalantly looking back at the camera, slightly flirting, slightly disinterested, it’s not quite right. It’s a performance work. On my dating profiles it gets worse… there’s a pic of me looking skinny in a dress with big sunglasses on; there’s the shot of me in FULL make-up just prior to a speaker event, looking up at the camera like for all the world I want to submit to you, happy. There’s one image of me grinning sideways at the camera as one of my children brilliantly ignores both me and the camera — i use this to flag that I have children, and that they are cute, regular, everyday kids. They are ‘normal’. There is one of me in front of a PRIDE symbol, in a (quite lovely) dress, on a beach, to tell you that I travel, or that I like the beach, or that I am into Pride, but mostly I feel awkward about this photo because I am fully supportive, active and passionately believe #pride, in lgbtq+ rights, yet this photo is one of a dozen, and I chose the photo that has an ever so subtle shift to my head, the possibility of a shrug, the hint of an eye-roll. I chose the photo that most explicitly outs me but that is also the most appeasing, the least confrontational kind of queer. I hedge my bets, I am visually as normal as possible. That has taken a lot of work…

I worry my photos betray deeper held beliefs in the unconscious qualities of subliminal signalling than any number of beguiling words. I was recently advised by a prestigious design body I had invited to join that my website was a little ‘ugly’. So now the home page is only words, which have the special ability to be ugly three ways: in the aesthetic of typography, in the quality of their prose, and in the ideology they espouse. There is nothing scarier than beautiful prose wrapped around ugly beliefs. And also nothing that better demonstrates that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

I feel safe behind words. But I manage my images far more carefully. Is it an assumption by me to suggest that none of us feel so safe behind our avatars? Like all forms of social performance, you can play the game or not play at all. You can switch and swap and be flighty, and silly and perhaps through this give us a glimpse at what insecurities that might foster; equally you may choose to hide (as I did literally) behind children or family members; you may always just be one face in a crowd, a candid shot of half a dozen grinning girls, or a quartet of boys in a bar. Perhaps you are simply turned away from the camera, a glimpse of a chin, the nape of a neck and some falling hair, like Richter’s enigmatic Betty; or tiny, distant and inaccessible -standing deep in the water of a still lake or adventurously half way up a mountain. Sometimes we strike a pose, conjuring an entire persona through stylised attitudinal cliches: the subgenres that used to be counter culture like goth, punk, anime, hippy, butch, and plenty of angry young women unwilling to be defined. There’s a box for that too. Often we cling to our partner, both of us happy in our collective bliss and the projected protection of the other. Sometimes it’s a comic strip. A cartoon likeness (particularly popular among the queer community it seems). An abstract image. A graphic icon. A cloud (yes, me. Sorry). Sometimes it’s a stupid meme. Or a political statement that is too small to read. Part of a movement. Sometimes it is rainbow-coloured, and I wonder is that an authentic gesture of support? A statement of alliance, or just filter-based clicktivism? Often, quite often, it’s just a picture of you, with a dumb grin on your face, being yourself. Being just you. Being open and true to the camera and I love those, I think because I find that honesty so impossible. One thing is for certain — in general — our avatars (away from the gaming community) are happy. We smile, grin, wink and laugh. We are the very best of ourselves. So in that there is already a lie.

Vicious eh? Well I don’t sit around pulling apart our avatars just for fun. Actually I hadn’t at all until this essay. But it is important to recognise the cognitive filters we use everyday and how many of those are visual. HR teams in large companies eventually realised that they shouldn’t include any images of candidates on CV’s because of the high level of unconscious bias towards those who cannot disguise a less privileged status, you know, like gender, or race. Personally I have an entertaining cognitive quirk, along with being trans, bi, and a tee-total, vegetarian introvert geek, I am face-blind. The technical term is prosopagnosia and it is a developmental condition from puberty, meaning I can recognise in a heartbeat a kid I went to primary school with thirty years ago, but will say hi to a local soccer-mum and talk to her happily until she reminds me that we already had this conversation 45 minutes earlier when we dropped our kids off at school. I can forget partners, or rather, never forget them, just lose that ability to associate faces. So I can flirt with people I still find attractive, yet no longer actually go out with. Which can get awkward. However my visual cortex is fine and I remember images and avatars of people far more readily than I do the actual person themselves. To me you are all your avatars. Unchanging, and hopefully close to your true self. When I went to have surgery to feminise my face my greatest fear was about no longer being recognised, not what might happen to me. Because if my friends don’t recognise me, and show me that with their body language, their face, their smile, then I simply don’t recognise them — which can be a lonely place.

So it all matters to me. These images. And it is also important to the trans-community, more important than you might imagine. Because for ever we have sought our own erasure — to be recognised as men or as women — and maybe that’s beginning to happen now, in the right way, sometimes. But for ever, whether in denial, or closeted, or out, we have aimed to fall on one side of the binary or the other. To pass. Not to be, to pass. The language is important. However to be neither, to be trans, to be between? That was not a safe position to adopt. Wherever you are on that spectrum. This is a community for whom, successfully coming out normally means that a majority never knows that you are, in fact, a minority. To be successfully trans has for many many years meant that you are invisible. So the only ’trans’ people we have known are those who are not successful, who embrace their visual non-conformity, normally within the confines of safe spaces online and off. These people used to scare me. In fact they still do. Men in dresses. The visibly transvestic, the butch queen, the obvious transsexual. Inspired a sensation of denial that I belonged there, which still sometimes feels like a fetish not a movement. A community that is identifiable only by images of people we cannot identify with is such a strange notion that I struggle to find a comparison? Which groups would put so much effort into disappearing, socially and visually? And I am sad to look at my own photos and realise that I still aspire to that. I struggle with the notion of disclosure around everyone, but mainly with men, (and especially with cute ones). I had hoped to include a fragment from my early diaries about the importance of this desire (historically) to be Cis-gender hetero-normative and disguise ourselves as normality. Unfortunately those attempts to capture my own internalised-transphobia from the beginning of my transition are still quite effective, and too distressing for me to share.

Instead I’d like to conclude with optimism. Five images of a queer person on a dating site that I found almost too honest for me to decrypt. The images felt generationally different, like hearing the Velvet Underground to my Bing Crosby. In the first photo our subject stares out blankly, body half-obscured by opaque glass, not smiling, quite androgynous. In the second we get a face hovering over a chess board, fiercely concentrating and positively masculine, the next two images are of the still the same person, yet somehow transformed; a startlingly pretty profile on a road in the Australian outback, and then that same woman on a mountain smiling down at a friend. Both are unambiguously feminine, and not sexualised. There is a shot of some legs dwarfed by a giant back-pack, to indicate a wilderness spirit and a love of the outdoors. The final photo is a sepia toned passport photo, straight on, emotionless, genderless — it reminds me of a mugshot of a revolutionary student from the 1970’s. Full of unparalleled confidence in themselves, their beliefs, and their own true self, unconcerned about the physical and, for that, unbelievably beautiful. The summary does not mince words either. There are no justifications, no allusion, just a frank profile, with only one word for me, half way through a list of attributes in the second paragraph. “Queer.” it says, “and open-minded”.

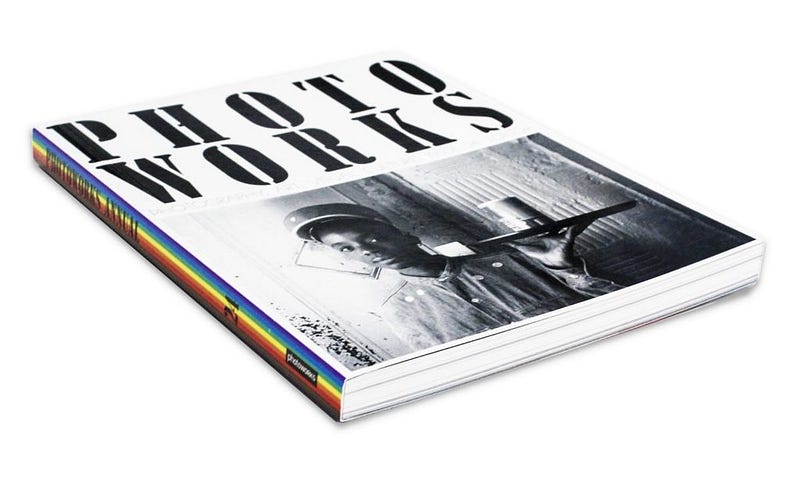

A shorter, better edited version of this essay first appeared in Photoworks